|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Saturday 31 January 2004

Random Interesting Thing

Band Names From Spam Two-word pairs, as they occurred in a recent piece of spam I got, with a subject line of ‘fabric paradoxic colette harpsichord oilcloth’. Some of these would make better movie titles than band names: extraterrestrial cyclorama Posted by tino at 09:10 31.01.04

Friday 23 January 2004

Random Interesting Thing

Junk Room Serendipity I spent some time today going through some boxes in the junk room and picking out things to haul to the dump. Among the things to go: Oracle 7 documentation, freebie CDs from trade shows seven years ago, lots of floppy disks, papers, bags, trash. We have a reasonably-sized room in the basement that’s almost completely filled, floor to ceiling, with banker’s boxes, and in those boxes you are liable to find anything.

One of the boxes — long since sorted and discarded — famously contained:

The box was labelled “Miscellaneous”. The problem is that few of the boxes have labels that are much more helpful than that. A good quarter of them are labeled, literally, “Random”, and a lot of the others have labels like “Gadgets (broken)” or “Wires, probably useless”. Somewhere in that room, there are at least three toasters, and one toaster oven. Some of those boxes are full of old newspapers — and I don’t mean ones with stories about us, or things like the Washington Post from September 12, 2001; those tend to get thrown away. I mean, they’re full of just random newspapers that were thrown in a box because we were too lazy to do anything else with them. We have paid movers to move such boxes from house to house. I once opened a banker’s box only to find that it was full of miniature bags of snack chips. Judging by the dates on the things, we’d moved that box three times. Anyway, once in a while you do come across a gem:

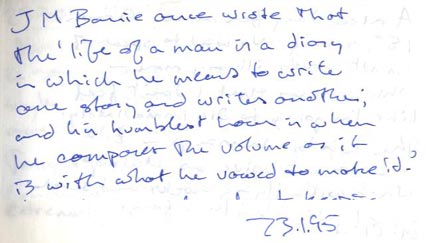

This is an excerpt from the first page of a diary I found in a box that otherwise contained old shopping bags. Particularly interesting is that this diary was begun exactly nine years ago today. I don’t generally keep a diary, so this is particularly serendipitous. It’s amazing the difference nine years make. In 1995, I had a gray BMW and a PowerBook. Now, I have a different gray BMW and a different PowerBook. The superficial details of my life don’t change all that much, I suppose. But nine years ago, I never would have guessed that today, I’d be living in the middle of nowhere in fucking Virginia and sorting through boxes of old junk. Some of today’s other activities drove home the theme of how time changes circumstances. One of the things I was trying to root out from the junk room was my collection of seriously obsolete software and documentation. I estimate that I threw away CDs, floppy disks, etc., etc. with an original retail value of about $20,000 (there were some copies of Oracle in there, which tends to push the price up pretty rapidly). Today, they’re worthless. The 80 mb hard drives I didn’t throw away; I just can’t bring myself to do it. They’re the blowtorches salted through this year’s generation of boxes, I suppose. It all makes me wonder — I realize that this is hardly going to come as a surprise to most readers — what I might be doing nine years from today, in 2013. I might be dead by then, of course, but the odds are against it. Presumably I’ll be chucking today’s 160 gb disks into boxes and sneezing from the dust. I only hope that some kind of hover-belt is invented by then, so I can do away with the step-stool. Posted by tino at 17:50 23.01.04

Tuesday 20 January 2004

Questionable Statistics

SUVs and Statistics The New Yorker is legendary for the rigor of their fact-checking department. They leave nothing to chance: A “Talk of the Town” piece once said that the musician Art Garfunkel had gesticulated nervously with his hands during an interview. Garfunkel later recalled getting a call from a New Yorker fact-checker asking if he still had both arms. That’s obsessive. So a recent Malcolm Gladwell article — entitled “Big and Bad: How the S.U.V. ran over automotive safety” — in the magazine is all the more puzzling. Gladwell has in the past shown himself to be a remarkably level-headed person; I’m sure that, like all of us, he has his biases, but in his writing he’s been very good about supporting his assertions with evidence. It appears, though, that his dislike of SUVs is greater than his dedication to honesty. I have rather a lot to say about this, with charts and graphs and all, to the tune of about 30 KB. (The New Yorker did not publish this article on their website. You just might find an 800K PDF version here, though.) Gladwell’s main thesis appears to be: The best strategy for automotive safety is to rely on active safety, e.g. the superior maneuverability of a sports car. Reliance on passive safety, of the kind you get by surrounding yourself with thousands of pounds of SUV, is at best illusory. He implies that this is a particularly American delusion. My guess is the Gladwell is correct, in a vacuum. His article does not prove this, though, and in fact at a number of points he contradicts his own conclusions. Gladwell bases his argument on several points: his experiences at the Consumer’s Union testing ground, an analysis of vehicular death statistics, and the comments of a French semiotician (really). The biggest problem, and what I spend the most time on here, is with the statistics, but the rest of the article is pretty baffling, too. The statistics appear to show (but don’t) that the larger a vehicle is, the more dangerous it is; Gladwell’s Consumer’s Union experience shows that SUVs don’t handle very well; and the French semiotician hints that SUV drivers might feel sexually inadequate. At Consumer’s Union, Gladwell drove two vehicles: a Chevy Trailblazer and a Porsche Boxter. At the outset, it must be observed that he is comparing a mid-range SUV built to price with one of the world’s most capable (and expensive) sports cars. It’s hardly surprising that the Boxster did much better in the handling tests than the Trailblazer. The Boxster was engineered from the ground up to be maneuverable; it seats two; and prices start at $42,600. The Trailblazer was engineered to be inexpensive and useful; it seats seven and starts at $27,420. These are very different vehicles, and it doesn’t really make sense to compare them. No one buys a car based solely on safety; fuel economy, utility, and price are important, too. Gladwell is really only discussing safety here: Most of us think that S.U.V.s are much safer than sports cars. If you asked the young parents of America whether they would rather strap thatir infant child in the back seat of the TrailBlazer or in the passenger seat of the Boxster, they would choose the TrailBlazer. He ignores that other factors — like the ability to haul more than one adult and that child — might be valuable, but as far as safety goes, he’s right. Provided that you’re paying attention, which you should be doing anyway, you are more able to avoid collisions, and thus potentially safer, driving a Boxster — or any sports car — than you are driving a less-maneuverable car like an SUV. So far, so good. Gladwell’s argument is weakened somewhat by the fact that he’s comparing extremes — a Taurus and an SUV would have been more convincing — but there aren’t any real problems yet. Statistics However, Gladwell then goes on to quote statistics. These appear to come from the study described here, and they appear to show that SUVs are, in fact, much more dangerous than other cars. These statistics are so flawed, though, it’s hard to know quite where to begin. Gladwell’s article contains a large table of a number of the statistics from the study:

This table as it stands does not really support the central argument that SUVs are particularly dangerous. The most-dangerous vehicle is the Ford F-Series truck, but the second-, third-, and fourth-most-dangerous vehicles are all quite small cars. No SUVs appear in the top eleven safest vehicles, but other than that they’re salted pretty well through the list. (If you sort the list by rates of death to people not in the vehicle in question, the worst vehicles are all SUVs — but not by much. However, one of the other criticisms of SUVs in the article is that they are bought by people who are “vain, self-centered, and self-absorbed”. A self-centered and self-absorbed person is by definition not going to give a damn what risk his vehicle poses to others, to there’s no mystery about the SUV’s appeal there.) One point of note is that SUV size doesn’t appear to correlate to hazard. The safest SUV on the list, the Chevrolet Suburban, is also the largest. The most dangerous, the Ford Explorer, is one of the smallest. The Chevrolet Suburban also proves to be significantly safer than the Chevrolet Tahoe — which is precisely the same vehicle, only shorter. Keeping in mind that these statistics are being offered to support an argument that large vehicles are not necessarily safer than small vehicles, you might start to scratch your head about now. But wait, it gets worse. You will note that these statistics are based on deaths per million vehicles, not deaths per million vehicle-miles, which is the usual metric for things like this. It’s not included in Gladwell’s chart, but the original study shows that the Ford Crown Victoria is far and away the most dangerous thing on the road, by any measure. This is because the vast majority of Crown Victorias these days are used as taxis or police cars, and as such spend an average of something like eighteen hours a day on the road. Obviously, the more a vehicle is kept in the garage, the less dangerous it’s going to be. I’m sure it’s possible to be killed by a stationary car that’s not running, but it’s not the usual way this happens. SUVs and pickup trucks are, on average, driven more than any other class of vehicle. The authors of the study point this out in their report: new SUVs, minivans, and pickups tend to be driven 7% to 14% more miles per year than new cars. In the very next sentence, they announce that this is a problem: Using annual miles traveled rather than sales would tend to increase our estimate of the risk in cars relative to that in SUVs, vans, and pickups […] Or, put another way, using miles traveled rather than vehicles sold would tend to make the estimates of relative risks more accurate, but they’re not really concerned about that. In a footnote elsewhere, they admit Annual miles driven probably is an even better measure of the “exposure” of vehicles to fatal crashes; however, these data also are not readily available by vehicle model. And, as we all remember from high-school science class, things that are difficult to measure are always insignificant, and can safely be ignored entirely. At least as long as ignoring those things tends to skew the results in such a way as to support our prejudices. Let’s all have a hand for science ladies and gentlemen! Hurrah! (And never mind that counting by number of vehicles and not proportional representation in the fleet is also going to skew the figures for expensive (and thus rarer) vehicles as a few particularly dangerous or particularly safe drivers will have a greater effect on the deaths per vehicle than they would were they driving very common cars.) Now, I’m not a scientist. I studied languages in college, for Christ’s sake. And even I notice that there’s a problem here. You can’t believe for a moment that the authors of this study, a professor of Physics at the University of Michigan and a researcher are Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, genuinely thought that these numbers would have any validity. Ah, but wait. Tom Wenzel, of LBL, has a master’s degree in public policy — which I believe amounts to ‘government’ — from Berkeley. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, but it calls into question whether his research is aimed at finding the truth, or whether it’s aimed at justifying a particular policy. And as for Marc Ross, of MIchigan, all we know about him is that he graduated from the University of Wisconsin in 1952. That he is (or was, actually; the university lists him as professor emeritus) a professor of Physics at the University of Michigan suggests that he should understand that these statistics are hardly scientific. Anyway, as I mentioned, I’m not a scientist, and I don’t have government grants or any graduate students to do research for me, so I am at something of a disadvantage. It occurred to me, though, that it should be possible to estimate the number of miles the average owner of a given type of car drives it in an average year by looking at used car ads. The online auction site eBay has a large section dedicated to cars, and it’s easy to search for specific makes and models there. This is hardly scientific: cars sold on eBay might tend to have higher mileage than the average; a number of other used-car-sales channels, such as dealer used-car departments and companies like CarMax, seek out low-mileage vehicles. For the used car with higher-than-average mileage, there are fewer sales channels available. Nevertheless, the comparison should be relatively accurate, since I used the same potentially-biased source for mileage figures for all the vehicles; while we might be missing out on low-mileage SUVs, we’re also missing out on low-mileage Toyota Avalons. I looked on eBay for 2000 model-year vehicles, and I noted the mileage on the top ten vehicles in the list — that is, the vehicles for the next ten auctions to end. I then computed an average four-year mileage for each type of vehicle. Some vehicles the list Gladwell excerpts were not produced in 2000, and some models had fewer than ten cars for sale on eBay, so not all the cars are included in my calculations. A few clear patterns appear:

Most of the vehicles are between 60,000 and 67,000 miles. Four are conspicuously lower, and five — three SUVs and a pickup truck — are noticeably higher. If we then divide the average mileage by the total number of deaths per million vehicles (as quoted by Gladwell) gives us a rather different ranking. This chart only includes the vehicles for which there were at least ten 2000-model-year versions for sale on eBay:

The standard measure of this sort of thing — the measure used by studies without an axe to grind — is incidents per million vehicle-miles, but as I am lazy I have just divided their number of deaths per million vehicles by the average number of miles driven for 2000 vehicles of the type. The number, described as “deaths per million vehicles per mile over four years” is itself pretty close to meaningless, but it’s a useful handicap of the deaths/million vehicles numbers supplied. The Toyota Avalon is still the safest vehicle, and the Ford F-Series truck still the most dangerous, but there’s now much less of a difference (4:1 before, now less than 3:1) The Chevrolet Suburban, the largest vehicle on the list, drops from 14th-safest to 6th-safest; and its slightly smaller cousin, the Tahoe, drops from 17th to 13th. The Nissan Maxima, Subaru Legacy, and Honda Civic fall quite a bit, from fifth, third, and fourth places to eleventh, fourteenth, and fifteenth. This chart shows the relationships in the rightmost column of the previous table. The yellow and pink columns are SUVs. You will note that

I have separated two of these SUVs out — the Suburban and the Tahoe — because they are the same vehicle. The only difference between the two is that the Tahoe is twenty inches shorter — and fifty-eight percent more dangerous. The SUVs are overrepresented on the high end of the chart — simple physics will demonstrate that a 5,000-lb. vehicle has more energy in it than a 3,000-lb. vehicle when moving at the same speed, and so more destructive force when it meets an Object At Rest, never mind anything about maneuverability. But there is clearly something at work here other than vehicle size. It might be the raw hatred of SUVs that seems to be tout ce qu’il y a de chic these days. Vitriol Read these questions from the New Yorker’s Q & A — an interview with Gladwell about the article — on their website. Remember, these are questions they ask Gladwell, not answers:

Gosh, now that’s some interview technique. The point of interviews is usually to find out what the other guy has to say. Leading questions are not necessarily always a bad idea, but this is just silly. It’s nothing, though, compared to what you find in the part of the article about Detroit’s house French semiotician: Over the past decade, a number of major automakers in America have relied on the services of a French-born cultural anthropologist, G. Clotaire Rapaille, I swear, some part of me still believes that this whole article is satire. Could The Onion do any better? An assertion that a truck doesn’t handle as well as a Porsche, some statistics that directly contradict the conclusion, and now someone named G. Clotaire to tell us what’s wrong with Americans. Over the past decade, a number of major automakers in America have relied on the services of a French-born cultural anthropologist, G. Clotaire Rapaille, whose speciality is getting beyond the rational — what he calls “cortex” — impressions of consumers and tapping into their deeper, “reptilian” responses. And what Rapaille concluded from countless, intensive sessions with car buyers was that when S.U.V. buyers thought about safety they were thinking about something that reached into their deepest unconscious. “The No. 1 feeling is that everything surrounding you should be round and soft, and should give,” Rapaille told me. “There should be air bags everywhere. Then there’s this notion that you need to be up high. That’s a contradiction, because the people who buy these S.U.V.s know at the cortex level that if you are high there is more chance of a rollover. But at the reptilian level they think that if I am bigger and taller I’m safer. You feel secure because you are higher and dominate and look down. That you can look down is psychologically a very powerful notion. And what was the key element of safety when you were a child? It was that your mother fed you, and there was warm liquid. That’s why cupholders are absolutely crucial for safety. If there is a car that has no cupholder, it is not safe. If I can put my coffee there, if I can have my food, if everything is round, if it’s soft, and if I’m high, then I feel safe. It’s amazing that intelligent, educated women will look at a car and the first thing they will look at is how many cupholders it has.” Good brakes make me feel safer. For G. Clotaire, what does the trick is apparently cupholders. Chacun à son gout. The problem with French semioticians is that they look too closely at everything, and they assume that everyone — except the French semiotician class — is deeply fucked up. A French Cultural Anthropologist will say that we have windows in our houses because we’re exhibitionists, and because we want strangers to see us naked like our mothers did while bathing us as infants: this is the (for)bidden. Me, I have windows so I can see out, and so I can save on the lighting bill. People like sitting up high in a car because they can see further that way, and being able to see what’s going on makes them feel safer. People like drink holders because they hold their drinks, which allows them to keep both hands on the steering wheel, which makes them feel safer. Intelligent, educated women look at how many cupholders a car has because they want to know how many goddamned cupholders it has. Sometimes a cigar, I have heard it said, is just a cigar. But not if you’re a French semiotician. Or, apparently, American journalist Malcolm Gladwell, who goes on to write: As Keith Bradsher writes in “High and Mighty”-perhaps the most important book about Detroit since Ralph Nader’s “Unsafe at Any Speed” […]That’s pretty dubious praise for the book, frankly; Unsafe at Any Speed was more about launching Nader’s career as a public scold than anything else. The book was about Detroit’s resistance to safety innovations in general, but it focused mainly on some design deficiencies of the Chevrolet Corvair. The book maintained that these design deficiencies were the result of a peculiarly American brand of greedy capitalism, despite the fact that Volkswagen had at the time been producing cars with the same design deficiencies — a front-mounted fuel tank and a swing-axle design that could cause the car to tend to tip over during particularly stupid maneuvering — for years. By the time the book was published, the Corvair design had already been changed by GM, but the bad publicity still sunk the car. Bradsher brilliantly captures the mixture of bafflement and contempt that many auto executives feel toward the customers who buy their S.U.V.s.According to this article, in 1999 the CEO of GM drove a Suburban — which might cast some doubt on how much ‘contempt’ ‘auto executives’ feel for SUV drivers. But never mind. Gladwell has more from Bradsher: Fred J. Schaafsma, a top engineer for General Motors, says, “Sport-utility owners tend to be more like ‘I wonder how people view me,’ and are more willing to trade off flexibility or functionality to get that.” According to Bradsher, internal industry market research concluded that S.U.V.s tend to be bought by people who are insecure, vain, self-centered, and self-absorbed, who are frequently nervous about their marriages, and who lack confidence in their driving skills. Maybe they’re gay, too. And probably ugly, and they have B.O. Where they hell are they getting this stuff (other than from French semioticians)? What is it about cars that causes people to feel the need to psychoanalyze others based on the things they buy? Why do people so resist believing that people buy the cars they buy because they like them? People might buy a certain car to fit in (or to stand out), or to communicate something that they believe about themselves; cars are very much like clothing in that regard. But while we judge people to an extent based on clothing, nobody would presume to say that someone who wears a certain kind of shirt does so because he’s insecure about his marriage. The New Yorker doesn’t run articles about the naiveté of people who buy high-profit-margin designer clothes; in fact, the New Yorker now has an annual ‘fashion issue’ where they celebrate the practice of paying a lot for clothing. I am not going to spend a lot of time trying to figure out why a certain class of people — usually people who publicly proclaim that one’s possessions are unimportant — is so wrapped up in what kind of car other people choose to drive. I will instead once again humbly suggest that the reason people drive SUVs is that calling something a ‘truck’ is the only way you can sell a type of vehicle that Americans appear to like to drive. The United States is different from most of the rest of the world in its taste in automobiles, for a number of reasons. Among them is certainly the relatively low cost of fuel here, but it’s important not to discount the fact that Americans spend a lot more time in cars than do people in most other countries. Your requirements for a car you spend 30 hours a week in are quite different from those for a car you spend four hours a week in. For whatever reason, Americans have long seemed to prefer much larger vehicles than people in other countries. The pleasure of driving a land-yacht or SUV isn’t the nuanced experience you get from a fine European sports car, but then there’s none of the noise and kidney-pounding, either. I own a fine European sports car, and I like it very much, thank you. I polish it with special cloths, and I tinker with the thing endlessly. The handling, the sounds, the smells, the entire experience of the thing is wonderful. But if I’m going to drive any serious distance — or if I have to take more than one other person with me, or if I have to haul anything — it really just won’t work. (Incidentally, my Fine European Sports Car gets about 15 miles to the gallon, significantly less than many SUVs; until they were met with a chorus of disinterest, the anti-SUVers refrain was that SUVs were inefficient.) So a lot of Americans want or need larger vehicles. This is hardly a fad; American cars have long been legendarily large and powerful. In a country with cheap fuel and plenty of parking, there’s no particular reason not to have a large vehicle if it’s going to be more convenient.

Americans did not start driving SUVs as a result of some marketing campaign, they started driving them because the vehicles that had formerly offered what the SUV offers had disappeared. Remember James Brown’s Cherokee, and OJ Simpson’s Bronco? A generation ago, both of these guys would have driven Cadillacs. By the laste 80s and early 90s, though, Cadillacs were underpowered, overpriced front-wheel-drive cars that were hamstrung by the government’s CAFE laws. The CAFE — Corporate Average Fuel Economy — standards require that the cars that a manufacturer sells attain a certain average fuel mileage. Obviously, this is a problem if you are Cadillac, and in the business of selling large and powerful cars to people who don’t particularly care about fuel economy. However, if your vehicle is a truck, you have to meet a different, less stringent, standard. So we wind up with the SUV, which is basically a station wagon built on a ‘truck’ chassis. What’s a truck? The EPA says: Light-Duty Truck (LDT) Any motor vehicle rated at 8,500 pounds GVWR or less which has a vehicle curb weight of 6,000 pounds or less and which has a basic vehicle frontal area of 45 square feet or less, which is: So if you build a Cadillac Sedan de Ville, you have to meet car standards. If you build a Cadillac Escalade, which is a derivation of the Chevrolet Suburban, which is in turn a derivation of the basic Chevrolet pickup truck, you have to meet truck standards, which are less stringent. This, and not any balderdash about sexual inadequacy, is why SUVs are so damned popular, and at the same time it’s why they’re less safe than passenger cars, to the extent that this is actually true. If you want to sell a large, powerful vehicle in this country, it’s much easier and cheaper to do so if the thing is legally a truck. Since it’s easier and cheaper to build, it’s easier and cheaper to buy. The SUV boom is the market’s adaptation to the government’s diktat that cars shall achieve certain fuel economy standards. One would think that the lesson to be taken from this is that the market is an incredibly powerful force, and that trying to overcome the will of the market will produce unintentional and possibly undesired results. Or, if you spin the numbers right, you can decide that what’s really needed is vilification of people who are just trying to get what they want a way they’re allowed to have it — clearly a state of affairs that calls for more regulation. Posted by tino at 17:40 20.01.04

Sunday 18 January 2004

Corporate Idiocy

Why We Love The Airlines, Part CXVII On a flight into Tampa:

So: the passenger is assaulted by a flight attendant — admittedly, it was a minor assault, but certainly it would have been enough to get a passenger arrested, had the roles been reversed — and the flight attendant makes a charge against the passenger that the police find to be unfounded. What happens?

Ahh, yes. Assault, making false reports: never mind. As long as it’s been established that a passenger hadn’t, you know, raised his voice or anything. Whew. The airline appears to have the same view of the incident:

So the airline will not discuss the particulars of this case where a member of their staff assaulted and made a false charge against one of the their passengers — one of their customers — but they will use the opportunity to warn passengers against annoying their staff — which the police determined didn’t happen in this case. Gosh. Maybe this attitude is part of the reason why US Airways isn’t profitable. In my experience, many flight attendants are rude and have this withering disdain for passengers; I’ve never seen a flight attendant assault anyone. But stories like this one are not rare, and it doesn’t take a whole lot of thought to figure out why. Flight attendants are, in 99% of their duties, flying waiters and waitresses. They give the speech about the oxygen masks, they bring you drinks and peanuts, and then they clear out the larger pieces of trash. In any other job, we would say: this is the job. In the case of the flight attendant, though, they’re told that their job is to ensure the safety of the passengers in an emergency. In truth, this justification is the result of lobbying by the flight attendants’ unions, aimed at making their members more indispensable. It’s worked: commercial aircraft are required by law to carry X flight attendants for every Y seats on the plane. If the pilot shows up but the flight attendants are stuck in traffic, the plane can’t legally take off. This is all fine; the whole point of the union is to make sure that its members have jobs. But when you take what is essentially a low-skill, low-pay job, require all kinds of training for it — training that has little to do with customer service — and dress it up in all this safety mumbo jumbo, you’re going to have frustrated people working that job. If you then give these frustrated, low-skill, low-pay people the opportunity to abuse their customers and broad powers to have these customers arrested if they don’t sit down and shut up, you’re going to wind up with a certain percentage of petty tyrants in the sky. Aside from being bad business all around, this kind of thing is dangerous as well. The airlines are losing money as fast as ever, but this kind of thing seems to be more tolerated today than it has been in the past, because of The Need To Fight Terrorism. But tell me: wouldn’t Fighting Terrorism be easier if you could be reasonably sure if a passenger who the flight attendants had determined to be a risk was, you know, actually a risk and not just someone who had bruised the flight attendant’s fragile ego? Does not the flight attendants’ lofty position as the Thin Beige Line protecting us from those who would hijack planes demand at least a little more professionalism from the flight attendants and their employers? Posted by tino at 12:09 18.01.04

Monday 12 January 2004

Copyright Issues

Counterfeiting, Adobe Photoshop, Copyright, and the Future - Part I A little over a month ago, I wrote something here that I illustrated with a picture of a pair of $5 bills.

This image would be impossible using the latest versions of the $20 bill and Adobe Photoshop.

Trouble is, the software doesn’t just prevent you printing accurately-representative copies of currency, it prevents you doing anything at all to images of currency. If you attempt to scan currency, or open a file containing an image of currency, or paste in something from the clipboard that contains an image of currency, it’ll refuse — even if you are using the Bureau of Engraving and Printing’s own ‘specimen’-marked samples.

In the U.S., at least, there are specific laws governing the use of currency images: you’re allowed to use them, as long as they are less than 75% of the ordinary size, or greater than 150%, and as long as they’re one-sided. But, given that Photoshop is the tool of choice for things like this, you are effectively no longer permitted to do so — and without any debate in Congress about it, either. It appears that this has to do, in part, with these little ‘20’s on the back of the new bill:

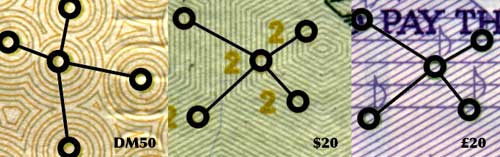

If you look at other currencies, you’ll find similar things, little circles in decorative or random patterns. But they’re not random at all, and their decorative value is secondary; on a lot of modern currency, you’ll find these little circles in constant relation to one another, like these:

You find the same thing on bills from a number of countries:

Now, what concerns me is not that this is going to put a crimp in my bogus-$20 operation. What concerns me is that there’s now a class of images that you effectively cannot make use of, even though such use is perfectly legal. There’s no defense for people who want to be able to make their own twenties, of course, but there are a lot of other uses for images of money. This move echoes what’s been going on in the copyright industry of late. The problem with counterfeit currency isn’t (usually) that there’s so much counterfeit currency floating around that the issuing bank goes broke redeeming bogus notes; the problem is that, the more counterfeit currency there is, the less people trust the stuff, and the less the currency is trusted, the less it’s worth. A copyrighted work — let’s say a DVD of Gigli — has its value diminished by counterfeiting, too. (More accurately, a movie has its value diminished by piracy in general, of which counterfeiting is just one category. For the purposes of this discussion, it’s all the same.) When Gigli came out in the theater for the first time, it cost you around $10 a head to see it. Currently, you can buy a DVD of it for $25 at Amazon, a DVD that you can watch time and time again, in the company of friends. Soon, you’ll be able to buy the DVD in the giant bin of B-movies at Wal-Mart for $3, and not long after that you’ll find it showing in the wee hours on the Hallmark Channel, interspersed with commercials for Tom-Vu-esque real estate scams, porn chat lines, and Billy Mays products. Every time the movie is shown, it loses a bit of value. The value of something like a movie never actually drops to zero — though in the case of Gigli, I’m not so sure that’ll be true — but certainly in the early years of a movie’s life, every person that sees the movie costs the studio something in that the value of the movie as a product is diminished. (Good movies are ones where this value diminishes the least every time it’s watched.) Columbia Pictures wants to make sure that they capture as much of this drop in value as possible in the form of dollars flowing into their bank accounts. The more unauthorized copies of Gigli there are out there, the more people can see the movie without any money going to Columbia, and the more money — in terms of the value of the unseen film — they lose: so Columbia opposes and fights piracy. However, much of the copyright industry, in fighting piracy, is these days taking the opportunity to expand its control of how its information is used, far beyond the control necessary to ensure the value of its product — in much the same way that the ham-fisted anti-counterfeiting software now built into Photoshop goes beyond what’s necessary to make the product useless for counterfeiters. Next: What this has to do with copyright Posted by tino at 11:40 12.01.04

Monday 05 January 2004

Corporate Idiocy

Intellectual Property, Control, and Profit Last night’s not-very-good episode of The Simpsons features, at one point, Milhouse grimacing in a peculiar way.

This looked familiar, so I turned to the web. Eventually, I found the original image, and in fact The Simpsons had been more directly aping the original than I’d even thought:

This is a Frenchman watching the Germans march into Paris on 14 June 1940. Now, as it turns out, this photo is in the U.S. National Archives, apparently having been taken by an Army Signal Corps photographer who was in Paris when the Germans arrived. The Archives’ information on the provenance of this photo is sketchy. I began my search, though, assuming that this photo had been taken by a photographer for Life magazine, since many of the best photos of World War II originally appeared in Life. I did some poking around and eventually came across the Life magazine photo archive. There are actually two different Life photo archives online, depending on what you want. There’s this, a hosey Flash-based site touting prints of their photos. That is, for a price, you can purchase a copy of, say, Eisenstaedt’s famous photograph of a sailor kissing a nurse in Times Square, printed from the original negative. Pretty neat. Of course, you can’t just buy a print from them. They’ll sell only “to approved art and design trade accounts, including art and photography galleries, museum shops, corporations, lifestyle retailers, designers, and architects.” If you are not in this rarefied group, and if you don’t want to buy at least three photographs to begin with, they don’t want to hear from you. You must go through one of their authorized dealers, which are located in at least twelve states. Well, then. Oh, and the prices? I have to assume that it’s a matter of ‘if you have to ask, you can’t afford it’. Nowhere on their website do they give any indication of what you might pay for one of these prints once you track down a dealer. One wonders why they even have a website for this product, given that the main purpose of the site seems to be to tell you to go away. I’m wasn’t interested in buying a print, though; I just wanted to see the photograph in question, so I could compare it to The Simpsons. Time-Life’s picture digital picture archive is here, and it’s run by Getty Images. Trouble is, random members of the public can’t search the archive, and you can’t even browse more than a very few images. Eisenstaedt’s Times Square picture, probably the most-famous photo Life ever published, is nowhere to be found among the tiny thumbnails featured on the site. The site promises that you can search (and presumably see versions of the images large enough to distinguish details) if you register for an account; so I registered, supplying them with all kinds of personal information. A little while later, I got the following e-mail:

I have not yet been contacted, presumably because this is some process that requires the intervention of a human. So, their position is this: I can buy their images as photographic prints, but not directly from them; I have to jump through some specific hoops. I can, presumably, view their images online, and I can, for a price, use them in my creative works, but to even see whether one of their images will suit my purposes, I must establish an account with them — and establishing an account is not just a matter of signing up. Oh, and they look forward to providing me with ‘exceptional’ service. I would say that they’re already providing me with ‘exceptional’ service, as most people who are selling things are eager to do so. Tiffany’s will send you diamond rings in the mail, provided you can pay for them. A process that involves so many obstacles certainly is an exception. Presumably, Time-Life is hysterically paranoid about their images being ‘stolen’ and used without permission or payment, but I have to wonder whether this makes any sense at all. It’s not as if it’s in Time-Life’s interest to hold these images close to their vest; the main reason these images are so valuable in the first place is that hundreds of thousands of copies of the things were printed in magazines. Eisenstaedt’s Times Square photograph isn’t actually all that good a photo, particularly compared to the rest of his work: its importance and value comes almost entirely from the fact that nearly everyone has seen it, and that it symbolizes the end of World War II more clearly for most Americans than anything that happened on board the U.S.S. Missouri. And it’s not as if they have any hope of really capturing every last bit of potential revenue here. The Times Square photo is readily available at low resolutions online now, and I seriously doubt that all of these people have paid the license fee. Were Time-Life to attempt to collect licenses from people using the photo, most of those people would just take it down. If Time-Life were assiduous enough in their enforcement, they might manage to suppress the thing altogether, and create a generation of people who see that photo as nothing more than a couple of people kissing in the middle of the street. Part of the difficulty of valuing intellectual property is that exposure of the product — sale, piracy, whatever — carries an opportunity cost that’s almost impossible to accurately calculate. If I can see the Times Square photo for free, I’m a tiny bit less likely to buy an Eisenstaedt book, a small portion of the revenue from which goes to Time Warner. If I can buy it for $1.00, I’m less likely to buy it for $10.00 later. And so on. While it’s impossible to accurately calculate the opportunity cost of exposing intellectual property, nobody appears to even try to estimate the opportunity cost of keeping all this stuff locked up. It’s a Wonderful Life provides one of the very few examples of a quality media product that hasn’t been rigidly controlled for its entire existence. It’s a Wonderful Life isn’t the best movie ever made, but it’s certainly the best-known movie of 1946: The Best Years of Our Lives, a much better movie, won Oscars for Best Picture, Best Actor, Best Supporting Actor, Best Director, Best Screenplay, Best Editing, and Best Music in 1946, but most people today are not familiar with it. It almost certainly makes less money for MGM today than It’s a Wonderful Life does for Republic. In fact, It’s a Wonderful Life has probably made more money altogether, despite effectively having been in the public domain from 1974 to 1994, than The Best Years of Our Lives. Why is this? It’s because It’s a Wonderful Life was, for a time, a cultural artifact rather than a product. People now purchase it — either outright or by watching a broadcast with advertising — not because the information contained in the movie is otherwise unavailable to them, but precisely because it isn’t. It’s familiar; George Bailey’s wild run through the town, the halting Auld Lang Syne, Zuzu’s petals, and all the rest are part of the American Christmas tradition. The kid who works at the video store who had never heard of Citizen Kane and who told me that they probably didn’t have it because ‘it’s an old movie’ has undoubtedly seen It’s a Wonderful Life fifty times. There’s a value in that, and a value that can be measured in dollars. Unfortunately, most companies in the intellectual-property business show by their actions that they are more interested in having more iron-fisted control than they are in having more money. Posted by tino at 15:28 5.01.04

Cultural Note

Headlines The interesting thing is not that one of the headlines on the front page of today’s Washington Post is “A Triumphant Landing on Mars”. The particularly interesting thing here is that this is not the largest headline on the page.

Of further interest is the story directly beneath the boxed Mars story, about how many people in China must rely on candles for light because of electricity shortages. Electricity production in China is controlled by the state, and the central planners have, surprisingly enough, misjudged the demand. The Post, of course, intimates that this may be the result of what little competition and liberalization have been introduced to the Chinese electricity business:

Ah, yes. If only people weren’t doing so many things and using so much electricity, there would be no electricity shortage. If only people would see the virtues of central planning, all these problems would go away. Posted by tino at 12:39 5.01.04

|